This is a chapter from the book Kotlin Essentials. You can find it on LeanPub or Amazon. It is also available as a course.

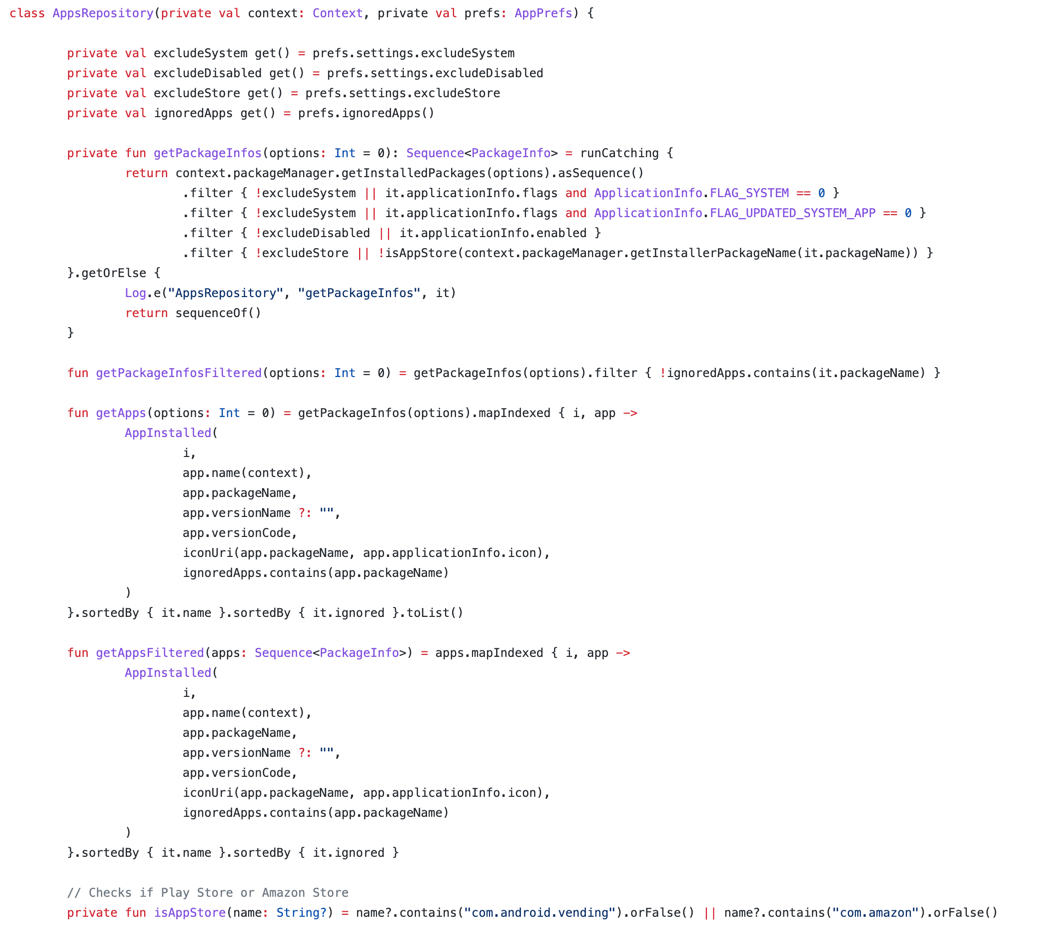

As an example, I used a random class from the APKUpdater open-source project. Notice that nearly every line either defines or calls a function.

fun keyword. This is why we have so much "fun" in Kotlin. With a bit of creativity, a function can consist only of fun:fun <Fun> `fun`(`fun`: Fun): Fun = `fun`

This is the so-called identity function, a function that returns its argument without any modifications. It has a generic type parameterFun, but this will be explained in the chapter Generics.

_, and numbers (but not at the first position), but in general just characters should be used.

In Kotlin, we name functions with lowerCamelCase.

fun square(x: Double): Double { return x * x } fun main() { println(square(10.0)) // 100.0 }

val a: Int = 123 // easy to transform from or to val a = 123 fun add(a: Int, b: Int): Int = a + b // easy to transform from or to fun add(a: Int, b: Int) = a + b

fun or when), use backticks, as in the example below. When a function has an illegal name, both its definition and calls require backticks.class CartViewModelTests { @Test fun `should show error dialog when no items loaded`() { ... } }

return keyword. The square function defined above is a great example. For such functions, instead of defining the body with braces, we can use the equality sign (=) and just specify the expression that calculates the result without specifying return. This is single-expression syntax, and functions that use it are called single-expression functions.fun square(x: Double): Double = x * x fun main() { println(square(10.0)) // 100.0 }

fun findUsers(userFilter: UserFilter): List<User> = userRepository .getUsers() .map { it.toDomain() } .filter { userFilter.accepts(it) }

fun square(x: Double) = x * x fun main() { println(square(10.0)) // 100.0 }

- functions in files outside any classes, called top-level functions,

- functions inside classes or objects, called member functions (they are also called methods),

- functions inside functions, called local functions or nested functions.

// Top-level function fun double(i: Int) = i * 2 class A { // Member function (method) private fun triple(i: Int) = i * 3 // Member function (method) fun twelveTimes(i: Int): Int { // Local function fun fourTimes() = double(double(i)) return triple(fourTimes()) } } // Top-level function fun main(args: Array<String>) { double(1) // 2 A().twelveTimes(2) // 24 }

isValid to false, in which case we should not return from the function because we want to check all the fields (we should not stop at the first one that fails). This is an example of where a local function can help us extract repetitive behavior.fun validateForm() { var isValid = true val errors = mutableListOf<String>() fun addError(view: FormView, error: String) { view.error = error errors += error isValid = false } val email = emailView.text if (email.isBlank()) { addError(emailView, "Email cannot be empty or blank") } val pass = passView.text.trim() if (pass.length < 3) { addError(passView, "Password too short") } if (isValid) { tryLogin(email, pass) } else { showErrors(errors) } }

fun square(x: Double) = x * x // x is a parameter fun main() { println(square(10.0)) // 10.0 is an argument println(square(0.0)) // 0.0 is an argument }

fun a(i: Int) { i = i + 10 // ERROR // ... }

fun a(i: Int) { var i = i + 10 // ... }

Unit, and the default result value is the Unit object.fun someFunction() {} fun main() { val res: Unit = someFunction() println(res) // kotlin.Unit }

Unit is just a very simple object that is used as a placeholder when nothing else is returned. When you specify a function without an explicit result type, its result type will implicitly be Unit. When you define a function without return in the last line, it is the same as using return with no value. Using return with no value is the same as returning Unit.fun a() {} // the same as fun a(): Unit {} // the same as fun a(): Unit { return } // the same as fun a(): Unit { return Unit }

vararg modifier. Such parameters accept any number of arguments.fun a(vararg params: Int) {} fun main() { a() a(1) a(1, 2) a(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) }

listOf, which produces a list from values used as arguments.fun main() { println(listOf(1, 3, 5, 6)) // [1, 3, 5, 6] println(listOf("A", "B", "C")) // [A, B, C] }

fun concatenate(vararg strings: String): String { // The type of `strings` is Array<String> var accumulator = "" for (s in strings) accumulator += s return accumulator } fun sum(vararg ints: Int): Int { // The type of `ints` is IntArray var accumulator = 0 for (i in ints) accumulator += i return accumulator } fun main() { println(concatenate()) // println(concatenate("A", "B")) // AB println(sum()) // 0 println(sum(1, 2, 3)) // 6 }

joinToString, which transforms an iterable into a String. It can be used without any arguments, or we might change its behavior with concrete arguments.fun main() { val list = listOf(1, 2, 3, 4) println(list.joinToString()) // 1, 2, 3, 4 println(list.joinToString(separator = "-")) // 1-2-3-4 println(list.joinToString(limit = 2)) // 1, 2, ... }

fun cheer(how: String = "Hello,", who: String = "World") { println("$how $who") } fun main() { cheer() // Hello, World cheer("Hi") // Hi World }

fun addOneAndPrint(list: MutableList<Int> = mutableListOf()) { list.add(1) println(list) } fun main() { addOneAndPrint() // [1] addOneAndPrint() // [1] addOneAndPrint() // [1] }

In Python, the analogous code would produce[1],[1, 1], and[1, 1, 1].

fun cheer(how: String = "Hello,", who: String = "World") { print("$how $who") } fun main() { cheer(who = "Group") // Hello, Group }

fun main() { val list = listOf(1, 2, 3, 4) println(list.joinToString("-")) // 1-2-3-4 // better println(list.joinToString(separator = "-")) // 1-2-3-4 }

class User( val name: String, val surname: String, ) val user = User( name = "Norbert", surname = "Moskała", )

name and surname positions; if named arguments were not used here, this would lead to an incorrect name and surname in the object. Named arguments protect us from such situations.fun a(a: Any) = "Any" fun a(i: Int) = "Int" fun a(l: Long) = "Long" fun main() { println(a(1)) // Int println(a(18L)) // Long println(a("ABC")) // Any }

import java.math.BigDecimal class Money(val amount: BigDecimal, val currency: String) fun pln(amount: BigDecimal) = Money(amount, "PLN") fun pln(amount: Int) = pln(amount.toBigDecimal()) fun pln(amount: Double) = pln(amount.toBigDecimal())

infix modifier, which allows a special kind of function call: without the dot and the argument parentheses.class View class ViewInteractor { infix fun clicks(view: View) { // ... } } fun main() { val aView = View() val interactor = ViewInteractor() // regular notation interactor.clicks(aView) // infix notation interactor clicks aView }

and, or and xor bitwise operations on numbers (presented in the chapter Basic types, their literals and operations).fun main() { // infix notation println(0b011 and 0b001) // 1, that is 0b001 println(0b011 or 0b001) // 3, that is 0b011 println(0b011 xor 0b001) // 2, that is 0b010 // regular notation println(0b011.and(0b001)) // 1, that is 0b001 println(0b011.or(0b001)) // 3, that is 0b011 println(0b011.xor(0b001)) // 2, that is 0b010 }

Regarding the position of operators or functions in relation to their operands or arguments, we use three kinds of position types: prefix, infix, and postfix. Prefix notation is when we place the operator or function before the operands or arguments[^06_8]. A good example is a plus or minus placed before a single number (like+12or-3.14). One might argue that a top-level function call also uses prefix notation because the function name comes before the arguments (likemaxOf(10, 20)). Infix notation is when we place the operator or function between the operands or arguments[^06_6]. A good example is a plus or minus between two numbers (like1 + 2or10 - 7). One might argue that a method call with arguments also uses infix notation because the function name comes between the receiver (the object we call this method on) and arguments (likeaccount.add(money)). In Kotlin, we use the term "infix notation" more restrictively to reference the special notation we use for methods with theinfixmodifier. Postfix notation is when we place the operator or function after the operands or arguments[^06_7]. In modern programming, postfix notation is practically not used anymore. One might argue that calling a method with no arguments is postfix notation, as instr.uppercase().

fun veryLongFunction( param1: Param1Type, param2: Param2Type, param3: Param3Type, ): ResultType { // body }

class VeryLongClass( val property1: Type1, val property2: Type2, val property3: Type3, ) : ParentClass(), Interface1, Interface2 { // body }

fun makeUser( name: String, surname: String, ): User = User( name = name, surname = surname, ) class User( val name: String, val surname: String, ) fun main() { val user = makeUser( name = "Norbert", surname = "Moskała", ) val characters = listOf( "A", "B", "C", "D", "E", "F", "G", "H", "I", "J", "K", "L", "M", "N", "O", "P", "R", "S", "T", "U", "W", "X", "Y", "Z", ) }

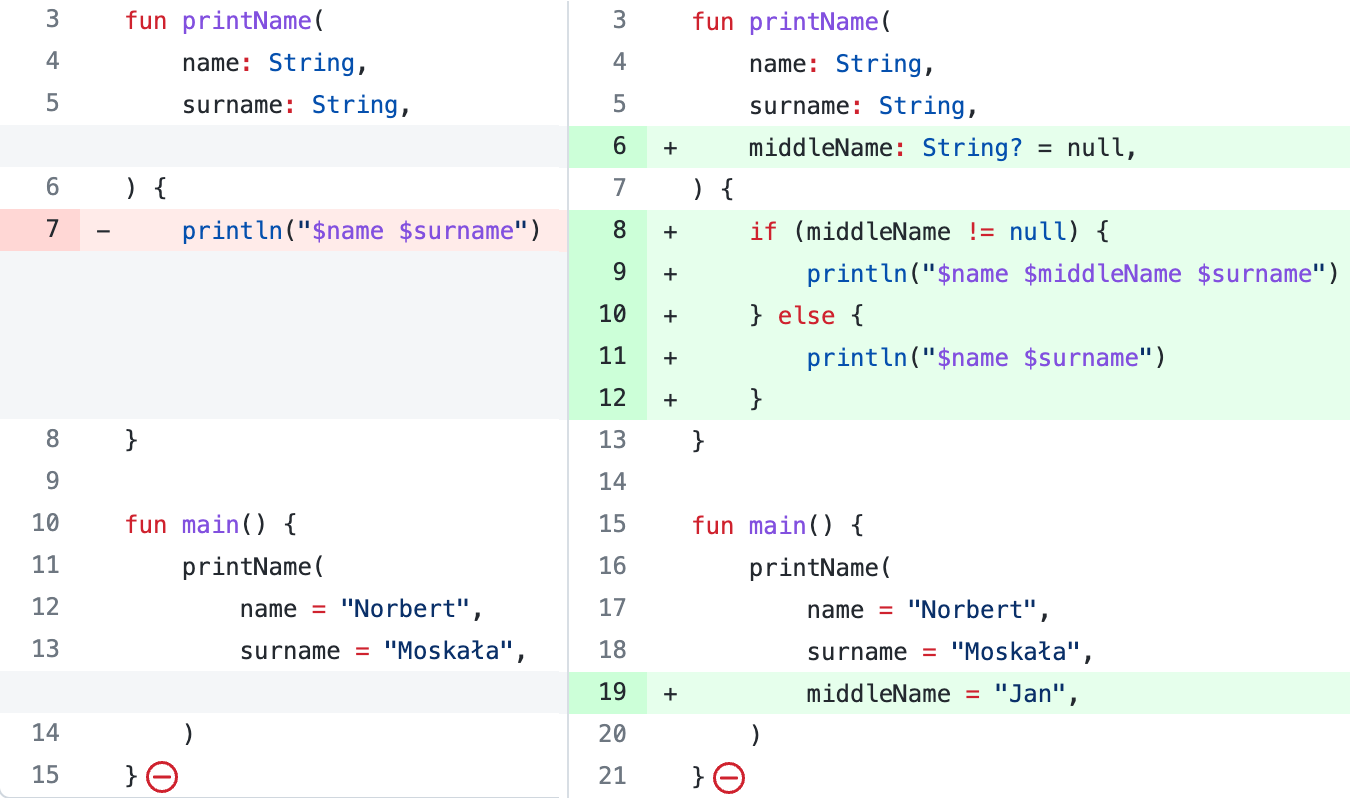

fun printName( name: String, surname: String, // <- trailing comma ) { println("$name $surname") } fun main() { printName( name = "Norbert", surname = "Moskała", // <- trailing comma ) }

Adding a parameter and an argument on git when a trailing comma is used.

Adding a parameter and an argument on git when a trailing comma is not used.

Unit result type makes every function call an expression. Vararg parameters allow any number of arguments to be used for one parameter position. Infix notation introduces a more convenient way to call certain kinds of functions. Trailing commas minimize the number of changes on git. All this is for our convenience. For now though, let's move on to another topic: using a for-loop.[^06_1]: Source: youtu.be/heqjfkS4z2I?t=660

[^06_2]: As a reminder, an expression is a part of our code that returns a value.

[^06_3]: See Effective Kotlin Item 14: Consider referencing receivers explicitly

[^06_4]: A constructor call is also considered a function call in Kotlin.

[^06_5]: We will discuss classes later in this book, in the chapter Classes and interfaces.

[^06_6]: From the Latin word infixus, the past participle of infigere, which we might translate as "fixed in between".

[^06_7]: Made from the prefix "post-", which means "after, behind", and the word "fix", meaning "fixed in place".

[^06_8]: From the Latin word praefixus, which means "fixed in front".