Item 27: Specify API stability

This is a chapter from the book Effective Kotlin. You can find it on LeanPub or Amazon.

Life would be much harder if every car were totally different to drive. There are some elements in cars that are not universal, like the way we preset radio stations, and I often see car owners having trouble using them. We are too lazy to learn meaningless and temporary interfaces. We prefer stable and universal ones.

Similarly, in programming we much prefer stable and possibly standard Application Programming Interfaces (API). The main reasons are:

-

When an API changes and developers get the update, they will need to manually update their code. This can be especially problematic when many elements depend on this API. Fixing its use or providing an alternative might be hard, especially if our API has been used by another developer in part of our project that we’re not familiar with. If it is a public library, we cannot adjust these uses ourselves; instead, our users have to make the changes. From a user’s perspective, this isn’t a convenient situation. Small changes in a library might require many changes in different parts of the codebase. When users are afraid of such changes, they continue using older library versions. This is a big problem because updating becomes harder and harder for them, and new updates might have things they need, like bug fixes or vulnerability corrections. Older libraries may no longer be supported or might stop working entirely. It is a very unhealthy situation when programmers are afraid to use newer stable releases of libraries.

-

Users need to learn a new API. This is additional energy users are generally unwilling to exspend. What’s more, they need to update knowledge that has changed. This is also painful for them, so they avoid it. It’s not healthy either: outdated knowledge can lead to security issues and learning what changes were made in those libraries the hard way.

On the other hand, designing a good API is very hard, so creators often want to make changes to improve it. The solution that we (the programming community) developed is that we specify API stability.

The simplest way to specify API stability is that creators should specify in the documentation that some parts of an API are unstable. More formally, we specify the stability of the whole library or module using versions. There are many versioning systems, though there is one that is now so popular it can be treated nearly like a standard. It is Semantic Versioning (SemVer): in this system, we compose the version number from 3 parts: MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH. Each of those parts is a positive integer starting from 0, and we increment each of them when changes in the public API have concrete importance. So we increment:

- MAJOR version when you make incompatible API changes.

- MINOR version when you add functionality in a backward-compatible manner.

- PATCH version when you make backward-compatible bug fixes.

When we increment MAJOR, we set MINOR and PATCH to 0. When we increment MINOR we set PATCH to 0. Additional labels for pre-release and build metadata are available as extensions to the MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH format. Major version zero (0.y.z) is for initial development; with this version, anything may change at any time, and the public API should not be considered stable. Therefore, when a library or module follows SemVer and has MAJOR version 0, we should not expect it to be stable.

Do not worry about staying in beta for a long time. It took over 5 years for Kotlin to reach version 1.0. This was a very important time for this language since it changed a lot in this period.

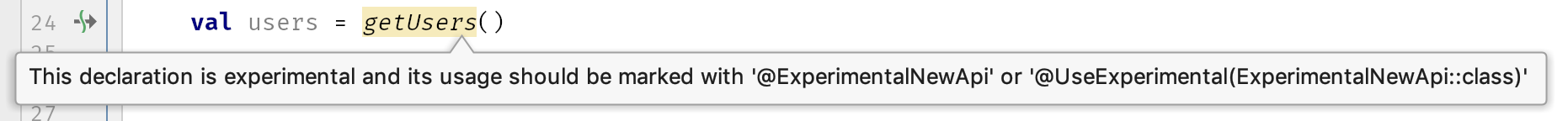

When we introduce new elements into a stable API but they are not yet stable, we should first keep them for some time in another branch. When you want to allow some users to use this API (by merging code into the main branch and releasing it), you can use the Experimental meta-annotation to warn them that it is not yet stable. This makes elements visible, but using them displays a warning or an error (depending on the set level annotation property).

@Experimental(level = Experimental.Level.WARNING) annotation class ExperimentalNewApi @ExperimentalNewApi suspend fun getUsers(): List<User> { //... }

We should expect that such elements might change at any moment. Again, don’t worry about keeping elements experimental for a long time. It might slow down adoption, but it gives us more time to design a good API.

When we need to change something that is part of a stable API, we initially annotate this element as Deprecated in order to help users deal with this transition:

@Deprecated("Use suspending getUsers instead") fun getUsers(callback: (List<User>)->Unit) { //... }

Also, when there is a direct alternative to the old function, specify it using ReplaceWith annotation, to allow the IDE to make an automatic transition:

@Deprecated("Use suspending getUsers instead", ReplaceWith("getUsers()")) fun getUsers(callback: (List<User>)->Unit) { //... }

An example from the stdlib:

@Deprecated("Use readBytes() overload without "+ "estimatedSize parameter", ReplaceWith("readBytes()")) public fun InputStream.readBytes( estimatedSize: Int = DEFAULT_BUFFER_SIZE ): ByteArray { //... }

Then we need to give users time to adjust. This should be a long time because users have responsibilities other than adjusting to new versions of libraries they use. In widely used APIs, this takes years. Finally, in a major release, we can remove the deprecated element.

Summary

Users need to know about API stability. While a stable API is preferred, there is nothing worse than unexpected changes in an API that is supposed to be stable. Such changes can be really painful for users. Correct communication between module or library creators and their users is important and is achieved by using version names, documentation, and annotations. Also, each change in a stable API needs to follow a long process of deprecation.